Patrik Staff Interview | Bon Magazine

Patrick Staff is the poster boy for an LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) generation that will not conform to or be confined by stereotypes. Splitting his time between London and Los Angeles, the twenty-seven year old artist’s interdisciplinary practice questions the categorisations of marginalised groups by an austere political system. Yet behind all the hype and the heavy sub text, you’ll find Staff mining labour politics, the queer body, social attitudes and how counter-cultures are shaped with the most effervescent attitude. Goldsmiths educated and shrewdly knowledgeable in everything from contemporary dance to Crip theory (about how bodies, pleasures, and identities are represented in relation to disability and queerness), Staff isn’t just another pretty art boy.

We meet in London’s east end, ironically at the Proud Archivist to talk about ‘The Foundation’, Staff’s most ambitious and complex work to date. Currently kipping in Dalston after being acrimoniously evicted from his studio due to London’s encroaching gentrification, Staff exudes the Californian calm of his new home town against the hubbub of Haggerston Riviera: ‘When you’re an artist in London you make sacrifices for the dialogue and the sparkiness. LA for me is queerer, it’s easier, and the quality of life is better. You chill a lot more.’

With Staff strategically positioning his practice, it was only a matter of time before influential curators and non-profit gallery directors would come calling. Staff has subsequently fostered productive working relationships with the likes of Catherine Wood (Contemporary art and performance curator, Tate) who included his multi-dimensional work ‘Chewing Gum for the Social Body’ in Tate Modern’s 2012 Tanks series ‘Art in Action’. While Emily Pethick (Director, The Showroom) showcased ‘Scaffold See Scaffold’ a workshop led project that foregrounded the body as the vehicle to construct diverse identities. And then there’s Polly Staple (Director, Chisenhale) who recently co-commissioned and exhibited ‘The Foundation’ which has firmly cemented Staff’s rising stardom.

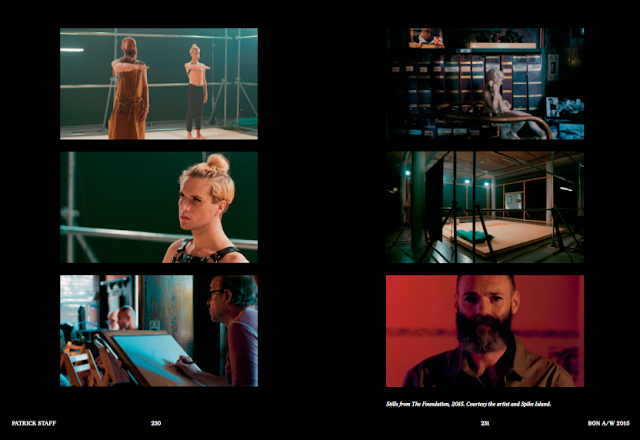

Shown within a darkened gallery that is only illuminated by a film projection, ‘The Foundation’ is an immersive and multifaceted installation. Insulation material is strewn across the floor, rolled in some areas to create potential seating. A rigging of scaff-like poles creates a support for the projection screen. These industrious materials are echoed in the film sequences of choreographed scenes between Staff and an older actor set within a minimally constructed set. And then there is the footage shot, sometimes on Staff’s iPhone, at the late Tom of Finland’s former home in LA. But this isn’t your regular artist’s home preserved for weekend tourism, it has become a dedicated foundation to the Finnish artist’s (aka Touko Laaksonen) homoerotic art where a gay commune live, work and play. Tight-framed interior shots of the house are interspersed with convivial clips of Bears hanging out. The bathroom is surveyed with the sink, some soap, an obligatory gay Grecian statue and a giant dildo. Domestic rooms have been converted into makeshift offices where correspondence is taking place. At one point someone, wearing archival gloves, opens the drawers of a plan chest to reveal the abundance of Tom’s creativity. Drawing after drawing of his archetypal buff, overtly male characters in lewd, explicit acts are pulled out.

The film draws on all of Staff’s prior experiences of working with minority groups and using bodily gestures as a form of expression. Most importantly this is not a documentary about Tom and the foundation. His legacy and diligent followers is merely a prism through which Staff is able to contemplate gender identity and queer intergenerational relationships. It also offers him the chance to work within the parameters of an exhibition and within a gallery context.

You might expect Staff to rest on his laurels whilst ‘The Foundation’ travels to the other commissioning sites: Spike Island, Bristol; Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane; and Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver: ‘In some way I guess I could put my feet up and let it tour until the end of 2016. But I think like lots of artists my self worth is slightly at its peak in the middle of a project.’ So he’s already planning his next collaborative project that explores the hormonal properties of plants.

Why do you think people are starting to take notice of you?

‘I guess I wandered into the Tom of Finland zeitgeist, his work is having this renaissance and people are excited which is funny because my work isn’t really about Tom of Finland.’

So how

did making ‘The Foundation’ come about?

‘When I was in LA for a small

exhibition in 2012, a friend said I should visit the Tom of Finland foundation

and check out the archive because I was making works about collectives and

alternative living. I went because it seemed anachronistic that the foundation

was in LA are not in Finland.’

Were

you a fan of his work?

‘I knew it although it's not one of my

references. I totally thought it would be a regular archive; white gloves, a

receptionist, you need an appointment. Actually it was when I turned up that I realised

it was this crazy three-storey house where you couldn’t tell who was living

there and who was working there. This guy welcomed me at the gates and asked if

I wanted some ice tea because “It's really hot.” I was given a tour of the

house, and the kitchens and bedrooms were given as much importance as the

archive. I was shown the dungeon with all its chains, slings and harnesses.’

Was

that Tom’s dungeon?

‘It’s the house’s dungeon and the

garden has shackles in it. The house has a urinal that when you piss in it, it

runs out to a shower in the garden, which they had rigged up themselves. They

were like: “The urinal isn’t working right now but we’ll fix it soon.”’

So did

you have an idea of what you wanted to make?

‘It was only really once I began

working away from the foundation that I began to understand what I wanted to

get out of it. It’s a complete artwork in itself. I was interested in the

history of Bob Miezer and Robert Mapplethorpe pushing to legitimise Tom’s work

and how that relates to my practice and what responsibility I have to these

historical materials. Also how the house started as a commune and at some point

formalised itself into an organisation and what it entails when the commune

members convert to employees. That was the stuff that got me hooked and got me

really like: “Fuck I need to work with these guys somehow.” ‘

‘The

Foundation’ might not be about Tom but it really emphasises a queer legacy;

both his and more generally.

‘Tom was a very real person to the guys

at the foundation, yet to me and to many others, Tom is just this spectre that

is never quite there. That's where this intergenerational thing gets really

complicated. Prior to the project I had been having conversations with older

gay male artists who had been belabouring this idea: “Well you need to carry

the torch, you have an obligation to our generation. Men of my age all died. You

need to carry on the legacy.” Within the queer community we talk a lot about

our chosen family with many people getting pushed out of the normal familial

structures, we start to reconstitute things and establish a family that exists

in its own way. So I have really been dealing with this and asking myself: “If

I am a child of this older generation what responsibility do I have?”’

And do

you feel responsible?

‘I've always really taken pride in the

fact that my community is diverse, it’s sexually and gender diverse, there’s a

range of sexualities, races and ages. Yet any community is dealing with how do

we look after ourselves. Do we shut the gates and preserve what we have and

protect ourselves from the outside world? And how do we remain open and how do

we change? That seemed like a really underlying question at the foundation.’

So what

did you want to achieve in the choreographed scenes with the actor?

‘The guy that I cast is totally

familiar with the world of Tom of Finland, he's a real ‘top daddy’ type and he

carries that in his body. I wanted to look at how the archive played out

through gesture and the way that the body moves? How does that information and knowledge

circulate through the materials in the archive, to the space itself and to the

bodies that inhabit it? That sort of plays out through lots of different

projects I've done but it comes most to a head in this work.’

‘It really varies between who watches it, amongst my peers people respond to the gender politics. There are certain other ephemeral elements to the work that people have responded to a lot. The clouds at the end get a really mixed and strong response. I’ve been surprised and amazed by how complex a reading it gets. The guys at the foundation got the most poetic and questioning about.’

Why is collaborating so important?

‘Originally it was a reaction to leaving Goldsmiths and suddenly being out in the art world. It was about being rebellious. It’s a lot more acceptable now, but then it wasn't the thing to do; authorship was golden and agency was key. I think it was also a certain reaction to feeling as if I had to produce a commodity even though I've never really dealt with the commercial art world. The first serious video work I made was with fifteen other people and I would doggedly argue that the work existed as raw footage on everyone’s own hard drives; the edit I might show is just one edit of many others. Stuart Comer, when he was at Tate Modern, asked me: “How do expect an archive or museum to be able to contain this work if it's spread between fifteen different people?” and I thought, “Huh, that’s the institution’s problem.” I’m not going to tow the line in that way.’

Collective authorship factors in many of your works. You worked with Olivia Plender on ‘Life in the Woods’ that took you around the UK devising strategies for alternative living.

‘Olivia and I were both really interested in reinvigorating people’s interest in intentional communities and back to the land way of living particularly post financial crisis. This was combined with an interest in queerness and queer paganism and various environmental ideas: rambling, the implications of trespassing on land, what's the history of the commons and how does that affect how we see public space, new forms of activism and a queer identity that is constituted outside of cities. We spent a year travelling around the country meeting crazy people and different communities. It was trying to figure out how we live now, how our identity and subjectivity is constructed.’

There

are multiple levels to you work. There’s the research, the active engagement,

the performative aspect, the documentation. How much do you consider all of

those things?

‘It’s really changed the longer I've worked and varies from project to project and with the group of people that I work with. I used to be interested in the set of conditions that led to the production of the work. Then I started to really feel the limitations of that. What originally felt pertinent and liberating – what really matters is what’s happening in this room right now and something will come out of it but let's not think about it – shifted. I guess now I want to do something a little bit more expansive.’

‘It’s really changed the longer I've worked and varies from project to project and with the group of people that I work with. I used to be interested in the set of conditions that led to the production of the work. Then I started to really feel the limitations of that. What originally felt pertinent and liberating – what really matters is what’s happening in this room right now and something will come out of it but let's not think about it – shifted. I guess now I want to do something a little bit more expansive.’

‘I think I get most drawn to the mediums that you can inherently push the limits with. For me I get the most tension out of choreography and dance and a certain amount of film and video.’

You

reference the choreographic work of Siobhan Davies and Rudolf Laban but there

is also a feel of Yvonne Rainer?

‘Yes completely, I think of Yvonne

pushing mattresses in her ‘Parts of Some Sextets’ in relation to the

installation of ‘The Foundation’. Steve Paxton is also really big for me in how

he developed contact improvisation and just let this choreography travel out

into the world. It's viral and rhizomatic. That relates to how I approach workshop

methodologies. Post-modern dance is totally important to me. I think choreographically

although dancers I work with are like: “You don't know anything.” But then I'm

like: “You guys know fuck all about art!” But then I’m a punk and an anarchist

and I don't need to know anything.’

‘For me it’s powerful to make everything malleable and to keep massaging a set of conditions until you can reformulate them, which is not to say that is always easy. It all comes back to that question of strength, this current government asks nothing more than for us to be infinitely flexible, and so does inflexibility become more powerful? Or does inflexibility render you a non-citizen? How can you be flexible without being manipulated? I don’t really know I just keep poking at thee questions from multiple points.’

I

wanted to ask about the quote on your website: Every cocksucker is well aware

that he same man who out on his badge to arrest him probably gets his blowjobs

at a different truck stop.

‘It’s a Patrick Califia quote, who is a

queer writer. I suppose it’s a little petulant, an antiauthoritarian thing and

a little bit of… [Staff finds it hard to put into words]. I still get people that want to be able to Google me and to get a

very concise summing up of what I do blah, blah, blah. And there is still a

part of me that is resistant to that. I’m not a brand, my work is not instantly

recognisable and there is a little bit of me that is: “Come and fucking deal

with it. Come and talk to me. Turn up and be in the room.” The quote is a good

way of dealing with the art world.’

© Freire Barnes

Originally published in Autumn/Winter 2015 issue of Bon